Where Are The Women of Wing Chun?

Created by a Woman, the Art of Wing Chun has Become Almost the Exclusive Domain of Male Practitioners.

By Joseph Simonet

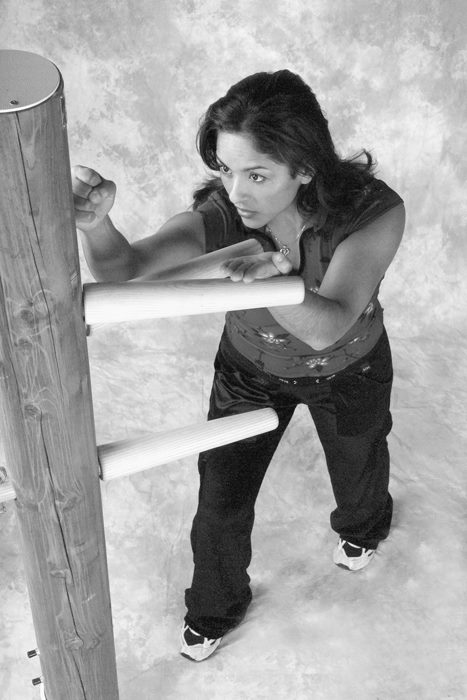

In this position, the bones of the forearm cross, bracing both the elbow and shoulder joints to create an extremely strong wedge-like structure. Once this alignment is achieved, the power of the body can be transmitted effectively to the arm through a quick, explosive rotation of the hips. When these elements are used in concert, the result is an incredibly powerful structure built upon skeletal alignment rather than muscular strength.

Sensing An OpeningAlso setting wing chun apart from other arts is its emphasis developing and using sensitivity in a fight. Through exercises such as chi sao and wing chun’s many trapping techniques, practitioners learn to “feel” an opponent’s intent before they see it. Once contact is made, the wing chun stylist uses his/her arms like antennae, sensing an opponent’s movements through instantaneous physical perception. This is much faster and more efficient than visual perception and, once again, helps the wing chun player stay a step ahead.

These elements can be used individually to give a fighter an advantage in a fight. However, if we combine them into a synergistic system, the result is an extraordinary fighting science that is structurally and tactically superior to many conventional fighting arts. Ng Mui and Yim Wing Chun created an art that allowed a woman with fewer physical attributes to easily defeat a larger and stronger man.

Since wing chun was developed by women and primarily for women, why has its lineage become so male-dominated? The answer is simple. Men also recognize a good thing when they see it. And since men also fear attacks by larger, stronger opponents, wing chun has great relevance to their self-defense needs as well.

Functional For WomenAlthough there are far fewer female wing chun practitioners today than males, traditional wing chun remains a practical and effective women’s self-defense system. However, in the original spirit of the art — to establish a system that uses structural superiority to overcome greater size and strength — I have modified wing chun’s traditional form to make it even more functional and adaptable to women’s needs. The result is “Extreme Wing Chun.”

The fundamental difference between traditional wing chun technique and that of “Extreme Wing Chun” is the use of the wu (guarding hand) as an active support for both offensive and defensive movements. I borrowed this concept from the serah style of Indonesian pencak silat (as well as some movements of tai chi) to further enhance wing chun’s superior structure and give the practitioner an even better chance of “evening the odds” against a physically superior attacker.

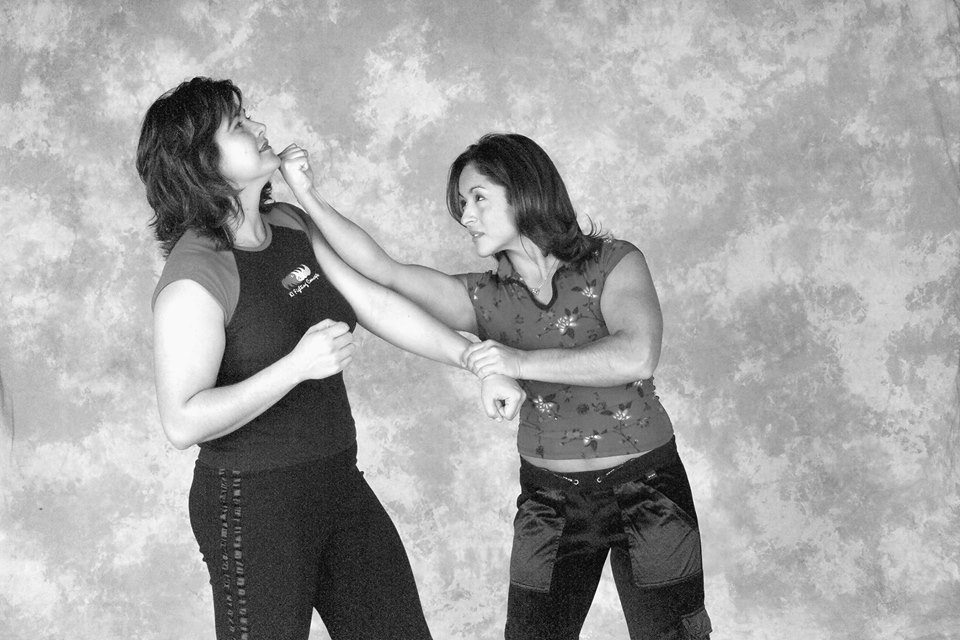

For example, let’s contrast a traditional wing chun tan sao (palm-up block) with the “Extreme Wing Chun” version. Normally, the tan sao relies on the structure of one arm to block while the other hand either guards or strikes. Against a right hook, the wing chun player might pivot left to block with a tan sao while simultaneously striking with a right straight punch.

The “Extreme Wing Chun” tan sao takes this concept a step further. By bracing the wrist of the blocking hand with the palm of the opposite hand, the strength of the basic tan sao structure is easily doubled and allows even women of very slight stature to effectively block full-power hooks thrown by much larger and stronger male opponents. At first glace, you might think this tactic sacrifices the ability to simultaneously attack and defend. However, rather than striking with the right fist to the head or body, the strike is actually delivered with the right elbow to the nerve cluster in the shoulder. Performed properly, this simple technique not only stops an attacker’s punch cold, it combines the offensive and defensive function of the tan sao into a single integrated movement that can almost effortlessly destroy the attacker’s arm and his will to fight.

The supported movements of “Extreme Wing Chun” help martial artists further enhance the already superior anatomical structures of traditional wing chun by adding the power of both arms to the technique without sacrificing the other advantages of the system. This approach works with all of wing chun’s core techniques, including the bong sao, tan sao, pak sao (slapping block), lop sao (pulling hand) and straight punch. Best of all, it continues the tradition of the art’s founder — seeking to develop and refine an art that offers the superior structure, timing, and training methods necessary to fight and win against larger and stronger opponents.

Photo Courtesy Knownows

Like all martial arts, Yim Wing Chun’s fighting system transcended the traditional arts of her time to achieve specific self-defense needs. Although the result was another worthy martial tradition, her greatest contribution was, in fact, her spirit of innovation and analysis. And that spirit is her true legacy — one that lives on in all women martial artists today and through the continued evolution of arts such as “Extreme Wing Chun.”

Do you want to work with us?

We are interested in finding new talent to work with us. If you have great work ethic, are diligent, and have a passion for design contact us.

And it doesn't hurt if your a Martial Artist!!